Humanities Crash Course Week 40: Good & Evil

Connecting with meaning by transcending cultural conventions.

Week 40 of the humanities crash course had me pondering deep philosophical questions. I read Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilych. and Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil. Both books were published in 1886 — and that’s not the only thing they have in common (despite also having many differences.)

I almost skipped Ilych, since I read it in college — or so I thought. But I went for it after all, and I’m glad I did: turns out I didn’t remember it after all, and ended up loving it. (As opposed to Nietzsche’s book, which I didn’t like.) For this week’s movie, I chose a classic inspired by Ilych. In contrast with last week’s pick, it’s become one of my favorites.

Readings

Let’s start with Beyond Good and Evil. Before I get into it, let me say upfront: I’ve always struggled with Nietzsche. I dislike the person that comes across in his pages, much like I dislike Marx. (And perhaps for similar reasons.) Yes, Nietzsche is the most important philosopher of the last two hundred years. But I often struggle to understand him: he seems more intent on provoking than clarifying. He’s a shitposter avant la lettre, and I don’t like shitposters.

So, the following summary comes more from my interactions with LLMs about the book rather than the book itself. (More on those below.) I’m in dangerous waters here: yes, I read the book, but I didn’t understand much of what Nietzsche was saying. I’m relying on my AI tutors to parse its meanings.

Nietzsche argues Christianity has infused Europe with a “slave morality” that cares for the weak, old, infirm, and social well-being at the expense of individual strength. Slave morality distinguishes between ‘good’ and ‘evil’. By good, he means the meek and harmless — i.e., downtrodden victims — and by evil, the powerful who oppress them.

He contrasts this with “master morality,” which instead distinguishes between ‘good’ and ‘bad.’ Here, good are the noble, life-affirming sentiments that build strength, and bad the weak and vulgar. Masters understand values are relative: rather than be ruled by constrained socially-imposed values, they establish values that give them advantages.

Nietzsche says adopting a slave morality weakens societies. He favors strength and power and argues for replacing Judeo-Christian values of egalitarianism, democracy, and pity — which he dismissively refers to as “herd morality” — with the “will to power.” Again, that’s what I got from my reading plus subsequent LLM interactions. This take might be wrong: I’m sure someone with a firmer grounding in philosophy could correct me.

Let’s move on to The Death of Ivan Ilych, which I understood better and which moved me greatly. In important ways, it stands in sharp contrast with Beyond Good and Evil. But it also shares important ideas with Nietzsche’s work.

Ilych, a respectable Russian middle class court official, has died. His wife, friends, and colleagues gather for his wake, but their thoughts are self-serving and superficial. The explicit subtext: they believe death can’t happen to them.

Ilych’s life is recounted in flashback. As a young man, he strives to fit in, quickly rising through the ranks. He marries. Happiness is always around the corner, but the family never has quite enough to live on, all jobs have downsides, the wife becomes ornery. They have several children, but only a daughter and son survive.

Eventually, he secures a better position and moves to a larger house, which he decorates to match his peers’ expectations – comme il faut. Always pushing for perfection, he falls from a stepladder and hits his side while correcting the work of a worker.

At first, he brushes off the accident. His wife and daughter are impressed and temporarily appeased by their new house. But the pain won’t go away. He consults fashionable physicians, but none give him a straight diagnosis. His wife and daughter read his pain only through how it affects them.

The pain increases and Ilych starts declining. Realizing he’s going to die, he revisits his life with regret. He’s lead a false existence pursuing the same superficial trappings as everyone else — comme il faut. He grows bitter. His hatred for his wife grows.

He keeps his feelings from everyone except a simple peasant servant, Gerasim — the only person in Ilych’s world who tells him the truth. He acknowledges Ilych is dying and tends to him, comforting and caring for him as his body wastes away.

Ilych spends his few remaining days mostly with Gerasim. In an ironic scene, his wife, daughter, and son-in-law go to the opera to keep up appearances instead of being with him. In his final hours, Ilych experiences a rebirth: he (literally) sees the light, regrets the suffering he’s causing his family, and decides to no longer struggle. He dies serenely. Heavy stuff!

Audiovisual

Music: Shostakovich’s Symphony 5, Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto 3, and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto 3. I was most familiar with the last of these, but all three were worthwhile.

Arts: Gioia recommended the Bauhaus, which I studied in architecture school (and therefore skipped now.)

Cinema: Akira Kurosawa’s IKIRU (1952), which was inspired by The Death of Ivan Ilych.

I love Kurosawa, but there are several of his key films I’ve never seen. This was one of them, and now seemed like a perfect time, given this week’s reading. Like Ilych, this story also features a punctilious public official who realizes he’s wasted his life after confronting a terminal illness.

Whereas Ilych finds redemption in self-renunciation and sympathy with his family, Mr. Watanabe (IKIRU’s protagonist) finds his in transcending the bureaucratic milieu that shaped his adult life to help a group of families build a park in post-WWII Tokyo. He, too, experiences a rebirth: Kurosawa includes Japanese children signing Happy Birthday in the background to drive the point home.

It’s a deeply moving story everyone should watch. I should’ve done so sooner, but watching now, at middle age, was especially affecting. The famous scene with Watanabe swinging in the snow had me bawling. I’ll definitely re-watch this, hopefully several more times (as I have other deeply inspiring films like AMADEUS and 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY.)

Reflections

When I first wrote that Nietzsche is “the most important philosopher of the last two hundred years,” I tried on a few qualifiers: arguably the most important, perhaps the most important, and so on. But really, the only other contender is Marx, but his influence is constrained primarily to social and economic institutions. Nietzsche changed everything.

We live in Nietzsche’s world: the idea that values are defined by perspective — and that you can roll your own — is the foundation for much of what goes by ‘liberal’ thought today. So it’s ironic that his ideas were so thoroughly perverted by fascists, who misread him (perhaps instigated by Nietzsche’s sister, an antisemite who edited his work posthumously.)

Nietzsche and Marx are (unwitting?) grandfathers to the two deadliest political movements of the 20th century: fascism and communism. I added a question mark because their rhetoric oozes hatred, resentment, and violence. Here’s a quote from Beyond Good and Evil:

Books for the general reader are always ill-smelling books, the odour of paltry people clings to them. Where the populace eat and drink, and even where they reverence, it is accustomed to stink. One should not go into churches if one wishes to breathe pure air.

And another (emphasis in the original):

What, then, is the attitude of [Christianity and Buddhism] to the surplus of failures in life? They endeavour to preserve and keep alive whatever can be preserved; in fact, as the religions for sufferers, they take the part of these upon principle; they are always in favour of those who suffer from life as from a disease, and they would fain treat every other experience of life as false and impossible. However highly we may esteem this indulgent and preservative care (inasmuch as in applying to others, it has applied, and applies also to the highest and usually the most suffering type of man), the hitherto paramount religions — to give a general appreciation of them — are among the principal causes which have kept the type of “man” upon a lower level — they have preserved too much that which should have perished.

ChatGPT tells me he’s writing metaphorically, that he means “spiritual and cultural vitality” and not human beings. But it’s not hard to see why eugenicists and other horrible people would gravitate to such passages. Like Marx, Nietzsche revels in provocation. Is it any wonder they bred monsters?

At first, I thought the Tolstoy novella provided a humanistic counterweight to Nietzsche’s icy amorality. Ilych and (especially) Gerasim represent compassion for and acceptance of weakness. But then, a series of insightful interactions with AI led me to understand they also share an important theme.

The overlap is in transcending culturally-imposed constraints and desires. Nietzsche argues you shouldn’t be subject to your culture’s values. Tolstoy argues that a life spent competing with the Joneses is a life wasted. At this level, aren’t this most deeply Christian writer and this most deeply anti-Christian writer alined?

Notes on Note-taking

As I said, I struggled with the Nietzsche book. And as a result, I spent more time trying to understand it than other readings in the course. I experimented with several ways of using AI. To start, I asked ChatGPT 5 for a high-level summary of the book as a whole. This was my prompt:

Please give me a high-level summary of Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil. Why does the book matter? What should I look for as I read it? Break it down chapter by chapter with a brief outline of the main points in each.

And here’s the response:

Nietzsche wrote Beyond Good and Evil as a sequel of sorts to Thus Spoke Zarathustra. It’s a sharper, more systematic attack on received morality, religion, and philosophy. He wants to explode the complacent “truths” of Western culture and clear space for a new, life-affirming philosophy.

The book matters because it:

Introduces Nietzsche’s most concentrated critique of philosophy, morality, and religion.

Sharpens ideas like the will to power, master vs. slave morality, and the revaluation of values.

Challenges us to think about truth itself: whether it’s worth more than illusion.

Lays the groundwork for later existentialism, postmodernism, and critiques of ideology.

As you read, look for:

Attacks on hidden assumptions: Nietzsche sees “truths” as masks for power.

Psychological analysis: he dissects motives behind systems of thought.

Style: aphorisms, provocations, paradoxes meant to unsettle you.

The call to create values: moving beyond inherited good/evil dichotomies.

Chapter-by-chapter outline

Nietzsche divides the book into 9 main parts (plus a preface and an aftersong).

Preface

Philosophy has been naïve: philosophers pretend to search for truth but really push hidden dogmas.

Nietzsche calls for a new “philosophy of the future” that unmasks these drives.

Part I: On the Prejudices of Philosophers

Critique of traditional metaphysics: philosophers smuggle in assumptions like “truth,” “being,” and “soul.”

Will to power as a deeper explanation of life than the will to truth.

Skepticism toward “free will” and “thing-in-itself.”

Part II: The Free Spirit

The “free spirit” breaks from dogma, especially religious and moral.

True independence comes from radical honesty and self-overcoming.

But free spirits risk isolation and nihilism.

Part III: The Religious Nature

Examines religion as psychological and cultural phenomena.

Christianity: a slave morality that glorifies weakness and resentment.

Monks and ascetics as “holy” forms of will to power.

Part IV: Maxims and Interludes

A series of short aphorisms: witty, cruel, often paradoxical.

Condensed insights into love, vanity, art, knowledge.

Read them as intermezzo—little flashes that echo bigger themes.

Part V: On the Natural History of Morals

Morality isn’t universal; it has a genealogy.

Distinction between master morality (noble, life-affirming) and slave morality (resentful, life-denying).

Morality as a tool of power struggles, not eternal truth.

Part VI: We Scholars

Nietzsche mocks the academic/scientific class.

Scholars think they’re disinterested, but they’re driven by herd instincts.

Science without philosophy risks becoming shallow positivism.

Part VII: Our Virtues

Nietzsche challenges modern virtues: compassion, equality, pity.

These may conceal weakness rather than strength.

Calls for a higher type of human who creates virtues rather than inherits them.

Part VIII: Peoples and Fatherlands

Thoughts on nationalism, Europe, Jews, and the future.

Critical of narrow national pride, but foresees a more unified Europe.

Often provocative and controversial—look for the interplay between culture and philosophy.

Part IX: What is Noble?

Nietzsche defines nobility as self-assertion, independence, capacity for creation.

The “philosophers of the future” will be noble spirits who revalue values.

The book crescendos toward the idea of a higher type who dares to shape humanity.

Aftersong

A lyrical closing, in verse. Nietzsche blends poetry and philosophy.

Why it matters now

It asks whether truth is always preferable to illusion—a very live question in an age of AI, media manipulation, and ideological battles.

It insists that values are human-made, not God-given—anticipating both existential freedom and today’s debates on pluralism.

It calls for a revaluation of values, urging us to ask whether our moral systems still serve life or whether they need renewal.

I used this outline as a guide when reading the book itself. Rather than read it all in one sitting, I read the summary of each part of the book before reading that part in the book. That kept me focused on that section.

As I usually do, I wrote my impressions in an Obsidian note after reading the book. This note also included AI-generated inline summaries. But when I fed this note into ChatGPT 5 (via the Copilot for Obsidian plugin), I realized my first take was highly reactive and mostly superficial. The ensuing chat helped me deepen my understanding.

I also tried a new (to the course) tool this week: Google’s NotebookLM, an excellent way to generate study guides. I uploaded PDF copies of both books to NotebookLM and told it I wanted the “Learning Guide” conversational style. This led to an enriching discussion with NotebookLM asking me insightful questions and giving me encouraging feedback.

One of NotebookLM’s most touted features is its ability to produce a podcast based on the study materials. I tried that as well, and it generated an insightful discussion comparing the themes of both books. I loaded the resulting audio file onto my Apple Watch using the WatchAudio app, and listened to it during my daily morning walk.

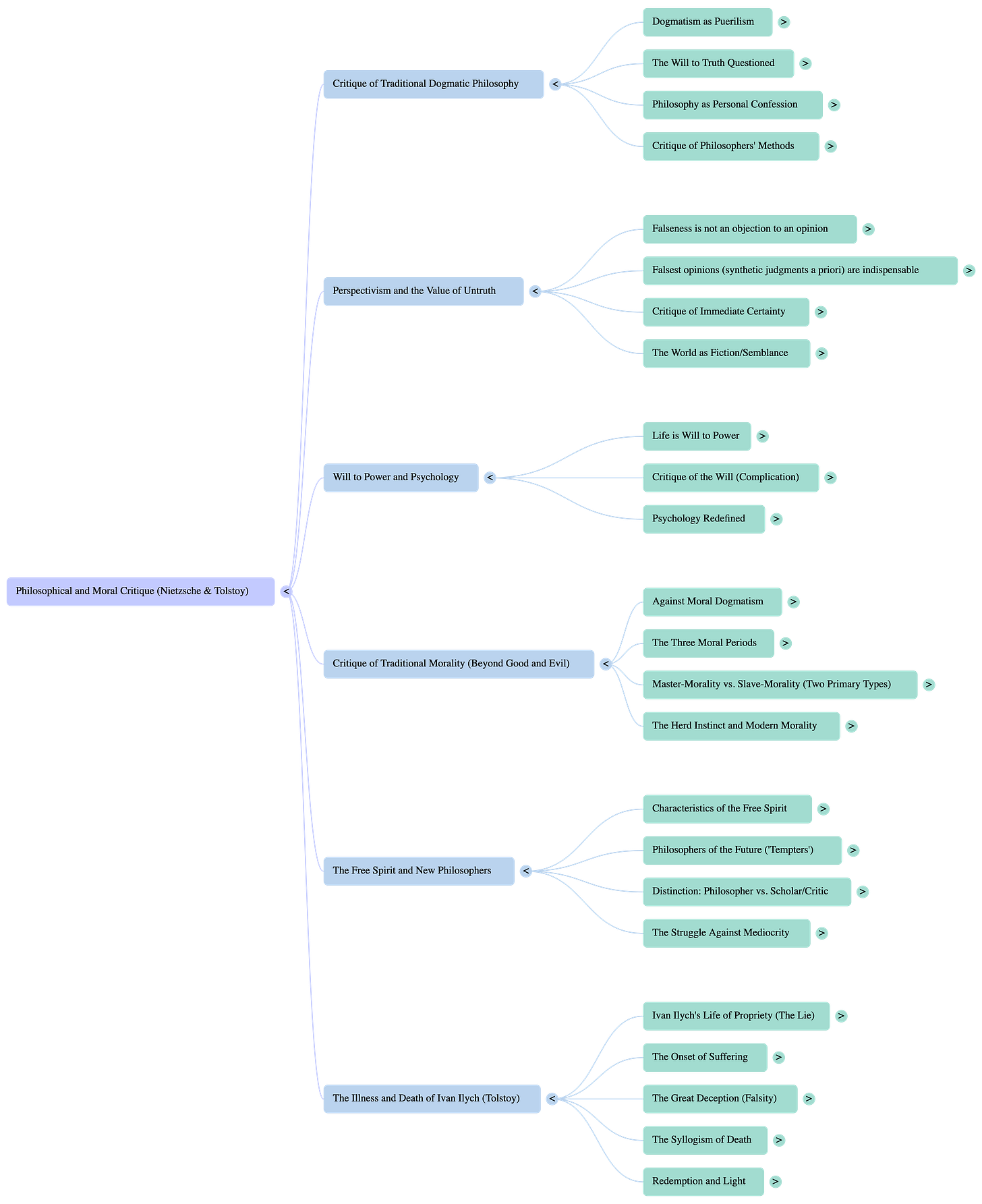

NotebookLM proved a powerful tool for learning this week. Unfortunately, I realized too late that it doesn’t save chats by default (like ChatGPT, Claude, and seemingly all other chatbots.) But in addition to the chat and podcast, it also generated this visual outline — nice eye candy to wrap up this week’s post:

Up Next

Gioia recommends Henry James’s The Spoils of Poynton and the “Overture” to Proust’s Swann’s Way. I’ve tried the latter and gave up after a few pages. As Gioia puts it, “get ready for long, complex sentences and full immersion into the psychological crises of the modern world.” Yikes! I’m spending lots of time in airplanes this week, so maybe this is good?

Again, there’s a YouTube playlist for the videos I’m sharing here. See you next week!

This post first appeared on my blog.